If you happen to come across a copy of Forest and Stream from the 1800’s there’s a chance you’ll see an article penned by a writer who goes by “Nessmuk.” If you read the article you might find a bit of ethics or philosophy cloaked in a topic like canoeing, woodcraft, or sensible camping gear. Beyond that, you’ll find a bit of 19th century humor, vivid descriptions of the wilderness, and the occasional barb to make sure you don’t leave without learning a thing or two. Without a doubt, Nessmuk’s work provides a unique perspective on life in the 19th century thats educational, entertaining, and easy to consume. That’s probably why Nessmuk (aka George Washington Sears), remains — to this day — one of the most iconic figures in the world of outdoor literature.

Now just because I said “iconic” doesn’t mean that he was perfect by any measure — or above critique. I you read his fairly famous book, your internal dialogue will drop a “WTF” from time to time. But, as a whole, Sears is a very interesting person who is worthy of discussion. After a bit of digging and reading you might see him as a renaissance man, and I can’t imagine I’d ever find an effective argument to the contrary. His writings reveal a man in search of perfect camping gear, a poet concerned about our impact on the environment, and a regular guy trying to figure out why on Earth people would ever want to squander their days in the “hustle and bustle” of modern urban society.

Oh, and if that’s not enough Sears also traveled up the Amazon river, inspired countless readers to enjoy the outdoors responsibly, and pretty much invented the idea of lightweight camping gear (or at least writing about it). So, that certainly qualifies him as a person worthy of a lengthy article (like the one you’ve bumped into today).

Camping in the 1800’s

Full disclosure, I have a hard time imagining outdoor recreation before the 1950s. Camping history in my mind comprises mostly personal experiences over the past 4-5 decades, photos of my late father in the forests of Montana from the 60’s and 70’s, and slightly crappier (but very similar) photos of his father post Second World War… in the forests of Arizona, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.

Beyond that I’m pretty much picturing Teddy Roosevelt and random characters like Daniel Boone. I wouldn’t be surprised if you’re in the same boat (or perhaps… canoe). I bet most of us today tend to imagine the 1800’s solely as a time of westward expansion, civil war, and the constant march of unregulated Industrialization. Thanks to history classes, movies, and television its pretty easy for most of us to conjure up a mental image of the events leading to the Civil War… or the tribes of the Western Plains… or even the railroads and the Alamo. But, up until about a decade ago I had no idea that in the years following the Emancipation Proclamation people were already heading out into the wild (often overloaded) to camp… or more accurately “glamp.”

People occasionally fled the city life to hire guides with canoes, or horses and mules to help move a huge amount of cookery, furniture, and luxury to the side of a remote stream, lake, or clearing. Other “outdoorsy” types ventured out to lodges on steam powered boats, but relatively few had really the luxury of both time and maybe the lack of funding to really connect with nature. At least the way that appeals to me and many of my fellow modern outdoor enthusiast. But, there were some like Sears, and they’re stories captivated me. Where did they go… did they hike everywhere? Did they sleep in tents… on the ground? How did they cook food while they were camping? Over the past five to ten years, questions like theses inspired me to read up on people like “Nessmuk.” And, today I’d like to share a bit of what I’ve learned.

What was the Outdoor Industry like back in the 1800’s?

I’m certainly not an expert on the matter, but from what I’ve gathered there wasn’t really an industry per-se. Aside from something like recreational fishing gear, most items one would take camping would be either custom made or sourced from another part of their daily lives. Your camp kitchen likely comprised items from home, or maybe you commissioned something custom from a tinsmith. Outdoor knives of the time were typically Bowies, modified kitchen / butcher knives, or folding pocket knives. If you look at limited advertisements in a publication like Forest and Stream you might find artificial flys, boats, retreats, and firearms. I even found an ad for a live moose in one issue (see image below), but have yet to see anything overly geared toward “just” camping.

Maybe we can attribute the lack of camping-specific gear to the “newness” of the hobby. Or perhaps the fact that a lot of people did what we now consider to be “camping” as part of their every day life or in their profession had something to do with it. Cowboys camped pretty much every night out of pure necessity. Logging camp cooks prepared meals outside and over fire, but I doubt they looked forward to it the way we look forward to cooking bacon and eggs next to a lake somewhere. Words like hunter and fisherman were more closely tied to someone’s profession than what they did on the weekends. And, canoes probably carried more trappers and beaver pelts back in the day than weekend “tramps” and “cruisers.”

But, despite the absence of glaringly clear distinction between profession and recreation like we have today – people like Sears sparked an interest in the public and set in motion an entire industry focused on gear made for outdoor recreation. For better or worse, we can now take into the wild a fork from the kitchen drawer… or something constructed of composite, stainless, or even titanium. From flatware, to tents, to packs (and much, much more) we’re absolutely spoiled for choice; and I like to think Sears played a part in that.

Sears’ Backcountry Gear and Gadgets

Sears loved his gear, but was certainly a minimalist. And, not just out of pure necessity, but because he realized that unnecessary weight his hard on the body and adds little to the overall experience. Chapter II of Woodcraft, 1884, covers his choices in gear quite well. It’s titled “Knapsack, Hatchet, Knives, Tinware, Fishing Tackle, Rods, Ditty-Bag.”

We, the “outers,” who go to the blessed woods for rest and recreation, are prone to handicap our pleasures in the matter of overweight; guns, rods, duffle, boats, etc. We take a deal of stuff to the woods, only to wish we had left it at home, and end our trips by leaving dead loads of impedimenta in deserted camps.

George Washington Sears (aka Nessmuk) – Aug. 1883

In Woodcraft sears mentions that he never carried more than 26 lbs into the wilderness. That includes his canoe, extra clothes, a sleeping bag, food for two days, his tiny pocket-axe, a fishing rod and pack. Looking back, that seems pretty incredible, but it is important to point out that a lot of things were sourced from nature. And they were “sourced” in a manner, that today… is unsustainable in most cases. Furthermore, I assume there was probably a bit of poetic license in his work. Either way, his philosophy was as valid then as it is now. Travel light and focus your spending on the things you truly need.

The Sairy Gamp – an 1800’s Ultralight Canoe

What the mule or mustang is to the plainsman, the boat or canoe is to guide, hunter or tourist who proposes a sojourn in the Adirondacks.

Forest and Stream, August 12, 1880 – Nessmuk

Sears’ passion for canoeing is woven into nearly all of his writing. He loved canoes and the freedom they provide. Unlike designs popular at the time Sears required that his boats be both sturdy and lightweight. This was fairly revolutionary at the time as most canoes of the era were fairly large and cumbersome. Some canoes, like those used by Lewis and Clark were absolutely enormous, one measures more than 30 feet long. Sears canoes, however, existed on the polar opposite end of the spectrum. He truly believed a solo paddler in a small, lightweight craft could cover more ground, access more remote areas, and enjoy a deeper connection with nature.

In the 1880’s, Sears commissioned renowned builder J.H. Rushton to build him something even lighter that the other lightweight canoes he’d built Sears. The result… the Sairy Gamp canoe, which weighed a mere 10.5 pounds. With this ultralight vessel sears embarked on a series of adventures chronicled in the 1883 Forest and Stream series “Cruise of the Sairy Gamp.”

The Nessmuk Knife

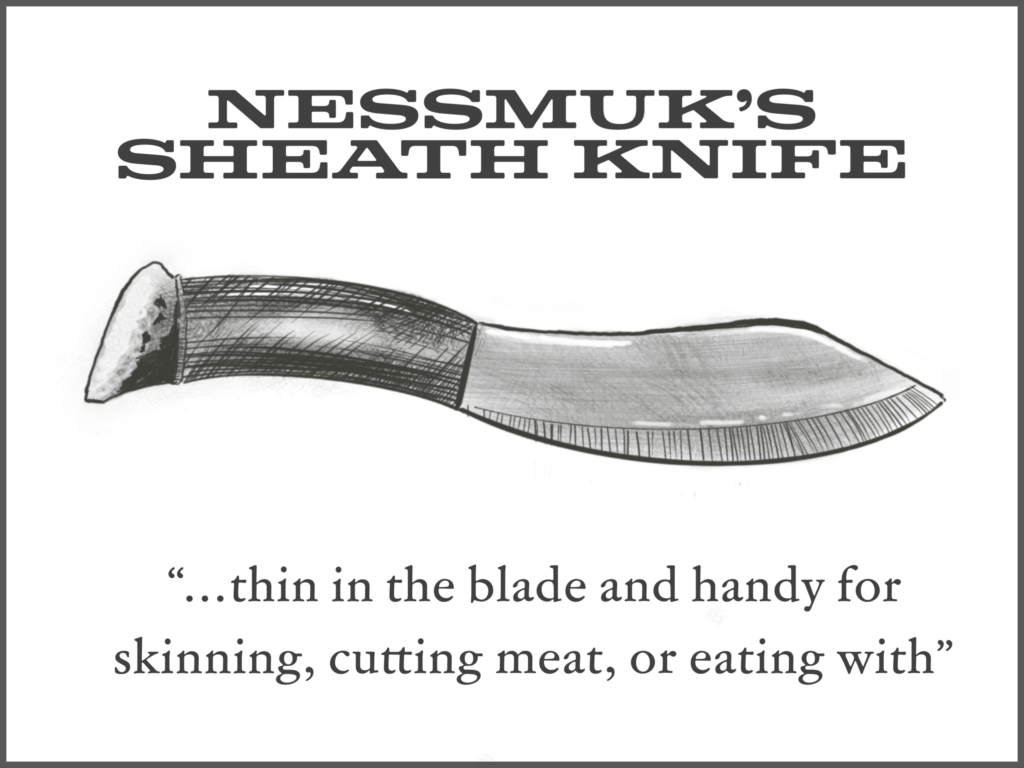

As a somewhat sensible gear junkie, one of my favorite Sears solutions is his 3 “blade” cutting tool setup for surviving and thriving in the backcountry. A double bit “pocket” axe, a belt knife (fixed blade), and a stout folder (he referred to it as a pocket knife) covered all of his basis. So, lets begin with Sear’s fixed blade. After all it is now a fairly popular design often reimagined that carries his pen name (Nessmuk). Be it a high end professionally made model, or a knife made in an afternoon with about ten dollars in materials the design lends itself to myriad tasks in the great outdoors. From meal prep, to processing game, to light duty chopping this knife is unbelievably practical in the backcountry.

In “Woodcraft,” Sears calls the Bowies and hunting knives popular in the mid to late 1800’s — “murderous looking, but of little use.” And while I don’t agree with him entirely, I would concede that for 90 plus percent of outdoor enthusiasts, a Bowie isn’t super practical. Sear’s fixed blade appears in a fairly well known illustration, but its origins (and exact dimensions) are up for debate. Some say it was a modified butcher knife, but it could also be something completely custom. In the years following the US Civil War most hunting and woodcrafting knives were either heavy duty folders, Bowies, or similar to a butcher knife. So the butcher knife theory definitely makes sense, but the curve in the handle also makes me wonder if the custom argument could hold more water.

So what makes the design unique? First and foremost it is “thin in the blade” according to Sears. Perhaps thats where the butcher knife rumors arose. Either way, for food prep or eating, a thin blade is miles better than most thick bladed knives. If you’ve every tried to cut an apple or prep some carrots with an Esee 4’s incredibly sturdy blade you know what I mean. Speaking of the Esee 4; at 9 inches9 it is roughly the same size as the Nessmuk according to most reputable estimates. Most modern designs that adhere to Sears philosophy build knives in the 3/32” to 1/8” inch range (e.g. the TOPS Knives Camp Creek).

Opposite the cutting and slicing end, you’ll find what appears to be a stag handle. Which given the time and location would be the most likely handle material. Personally I prefer the look of wood like you’ll see in knives like those made by Lucas Forge. Though I am really drawn to modern interpretations on knives like the Esee-JG5’s sculpted Micarta handles designed by James Gibson. And, given that Sears was a practical guy I’m guessing his modern knife would feature a man made handle that is stronger, more stain resistant, and longer lasting that an antler.

Back to the business end, the most forward section of the blade is the area that really makes a design stand out as Nessmuk-inspired. The upswept blade edge, backed by a shopping hump really makes the knife stand out in a crowd. It also packs more cutting edge in a shorter overall length and similar designs tend to skin large game animas quite well.

So, while I absolutely love the looks and history of the knife… the question I’d have to ask myself is as follows. We live in an age with myriad choices in fixed blades… would I Carry the Nessmuk into the backcountry? Absolutely. In fact, I plan to purchase a Nessmuk inspired knife as well as a Kephart… or um, two. It wont have a stag handle and I’m not sure how well it will work for food prep. But it worked for Sears, so it’s worth a shot in my humble opinion. Would you try one?

Nessmuk’s Pocket Knife

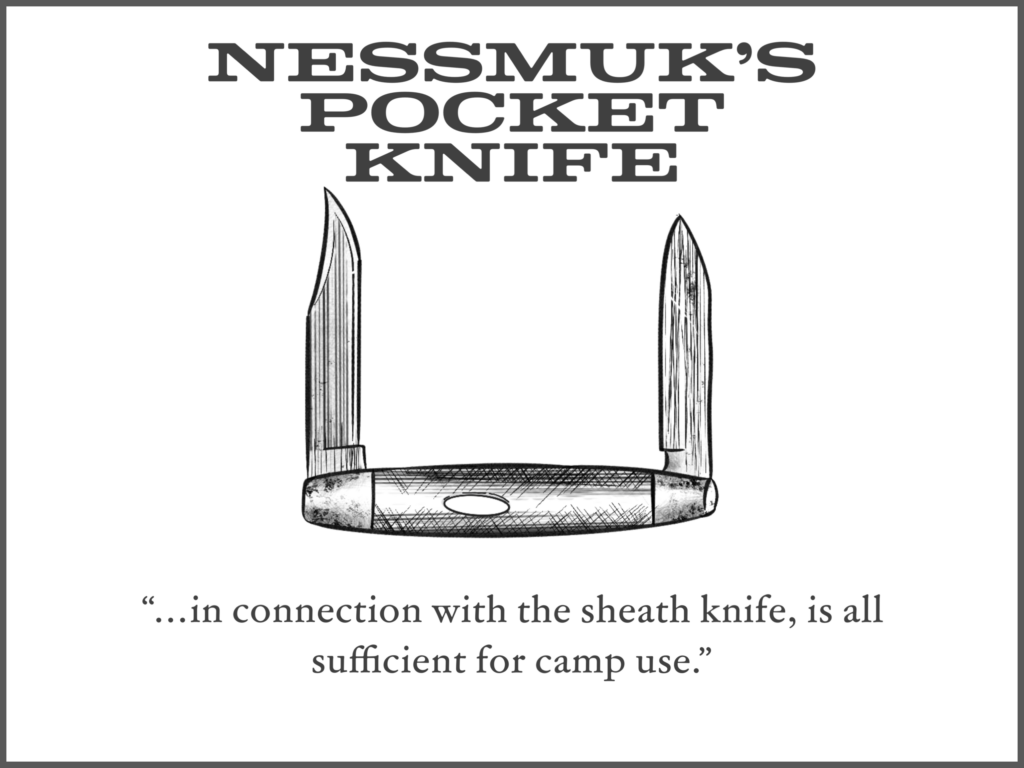

In the same illustration as the knife mentioned above you’ll find a double bit hatchet, and a small pocket knife. The pocket knife has two blades and looks pretty similar to those old school slip joints from companies like Victorinox, Buck, or Old Timer. The exact make and size is unknown… but Sears does allude to the fact that the pocket knife is robust and of good quality. Speaking of…you could also opt for a classic looking strong single blade option like the Kershaw Federalist or Case Sodbuster.

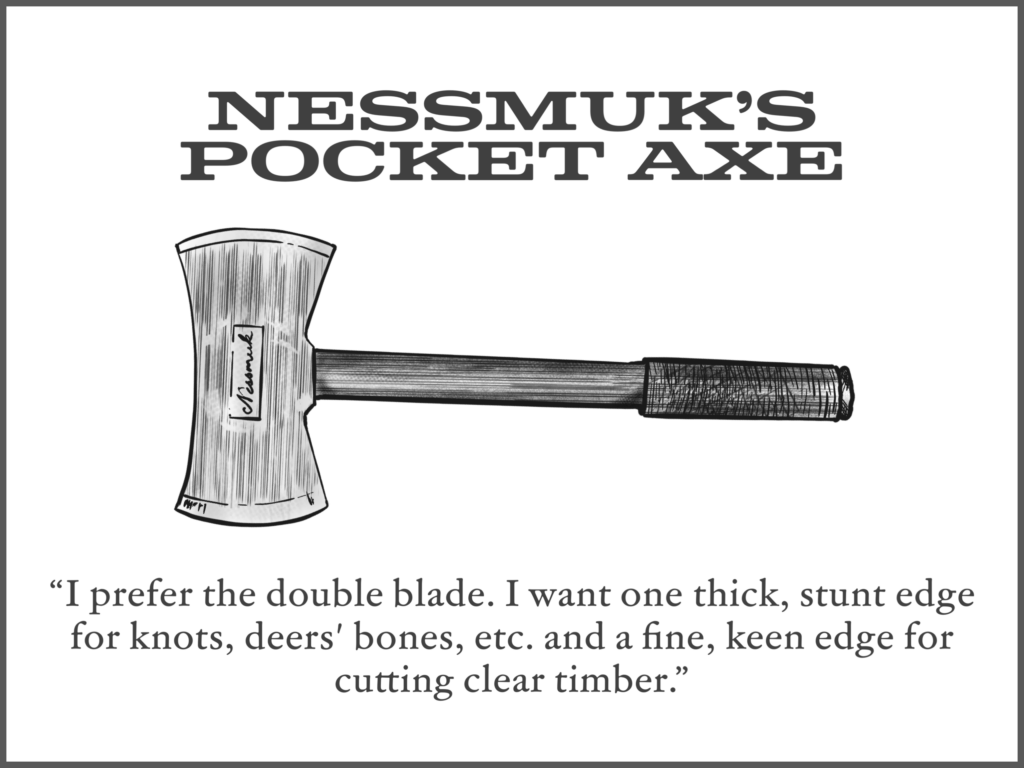

Sears liked the smaller format knife for more intricate tasks and tasks where the belt knife might be a little too large. Having two extra blades in his kit also spreads out the wear on the cutting edge between three rather than relying solely on one blade for all tasks. This approach is also seen in his double bit axe, though as I’ll mention below… probably isn’t the safest or most practical option for replicating Sear’s trio.

Would (or do) you carry an old school folder into the wilderness? I’m always changing this up in the pocket knife department, so I would like to try one someday. But, if I’m being honest with myself and could choose only one folder it wouldn’t be one like this. If there could be only one pocket knife in my collection it would probably be a Swiss Army Knife, a Spyderco, or something from Chris Reeve Knives if my budget allowed it.

Nessmuk’s Hatchet

Sears loved his “double barrel” hatchet. In fact he used a ton of others before landing on this custom made beauty. Sears says it took him about 12 years to land on this design, which he had custom made by a surgical instrument maker by the name of Bushnell. One side was sharp for finer cutting tasks and the other less so for more abusive work like cleaving bone.

Nessmuk’s Blanket Bag

The “Blanket Bag” offered sears warmth and is mentioned throughout his writings. He describes it as “open at both ends” and barely long enough to cover him while sleeping. He also mentions that it is made of Mackinac which you might now know as Macinaw Wool (made famous by Filson’s 1914 Cruiser that’s a take on the 1811 Hudson Bay Mackinac Jacket… made from Hudson Bay Point Blankets).

Michigan’s (and its neighbor to the north’s) fur trade and timber boom in the 19th century for the iconic and incredibly and practical cloth. It’s heavier than most woolen textiles… perhaps a little less plush. I imagine Sears’ was about as comfortable as the one “Uncle Sam” provided in my plush squad bay accommodations in San Diego, California decades ago. Regardless of comfort this cloth is very breathable and will keep you warm whether it’s wet, cold, or both at the same time. The name for the cloth comes from the Mackinac region where you’ll find the Straights of Mackinac (connecting Lake Michigan and Huron), Mackinac Island, and Mackinaw Michigan.

While the wool used in Sears’ Blanket bag traces its roots to the Hudson Bay Company’s Mackinac Region trading post established around the turn of the 18th century — there are many modern options available if you don’t want to opt for a down filled bag from your local big box outdoor retailer. Companies like Pendleton, Woolrich, and Johnson Woolen Mills are all privately owned companies that will scratch that heirloom quality wool blanket itch. My family has several Oregon-made Pendleton blankets and they’re outstanding, though we would love to try another brand (perhaps one in the buffalo plaid patter that warmed Nessmuk on chilly New York nights next to the water).

Knapsack (Pack / Backpack)

There are bags, modern and vintage, that capitalize on the Nessmuk name. Companies like Frost River, Abercrombie (the original… not the apathetically-staffed shopping mall hell hole it morphed into), and Woods Pack Company to name a few. Unlike the knives… information on Nessmuk’s pack is pretty sparse. Which is probably why some of the “reproductions” and “tributes” tend to vary in their design.

What we do know is that Sears claimed that the knapsack “holds over half a bushel.” Which should be around 18 liters if a bushel is 8 dry gallons (or a little over 35 liters). He also states that the empty weight of the pack is 12 ounces. Which is a little surprising given that Deuter’s modern 17 Liter Speedlight pack weighs almost 14 ounces (390 grams).

Horace Kephart an incredibly well known outdoorsman, writer, and friend of Sears said the following about the knapsack.

The so-called “Nessmuk” pack sack (he did not design it) is shown in Fig 31. It is made of medium-weight brown waterproof canvas. The bag has boxed sides that taper from about 5 inches width at bottom to 3 inches at top (not show in illustration) and it is about 3 inches narrower at the top than at the bottom. To the top edge of the bag proper is sewed a throat piece like that of a duffel bag. When the bag has been packed, this throat piece is gathered together and tied like the mouth of a gran sack, so as to exclude water

Kephart, Camping and Woodcraft: Volume 2 – Woodcraft

From what I’ve read online and experienced firsthand… I’m not sure that I could justify replicating the pack as described by Sears or Kephart. Especially the thin lightweight straps that Kephart called

I would, however, absolutely love a quality bag from Frost River, Duluth Pack, or similar in a classic pattern like the formers “Nessmuk” or the latter’s 34 L Cruiser. Bigger might be better these days since one cannot just go out into the forest and start chopping down trees for shelter and shooting deer for dinner like they did back in the day.

The Sailor’s Ditty Bag

Sears’ “EDC” as many now call it resides in a leather ditty bag that he wore “as often as (his) hat.” The bag made of chamois leather measures about 6×4 inches and carries a variety of gear. From fishing hooks and line, to pain medication, to buttons and sewing gear — Sears “Everyday Carry Bag” covered a wide array of needs. The bag also serves as a place to stash things like a compass, matches, or anything small that needs a temporary spot to live when one needs both hands.

Other Gear and Gadgets

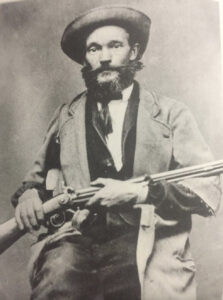

Sears’ Rifle, at least the one we know about, was quite unique by todays standards. In Woodcraft, Sears mentions that it is an incredibly accurate Billinghurst muzzle loader. William Billinghurst, of Rochester New York, established himself as a a maker of incredibly accurate rifles. In 1837, after the death of his mentor and employer, Billinghurst set out on his own making revolving black powder rifles based on the 1829 J&J Miller Revolving Pill Lock Rifle. Later Billinghurst expanded to create other innovative designs such a the rotating breech over-under and a twin barrel rifle fired by independent hammers.

Keen eyes in some of the forums mention that Sears’ rifle in the image, below is an “under hammer” and had two barrels. One fired by the hammer in the traditional location above the receiver, the other fired by the second hammer beneath the receiver in front of the trigger guard. An incredibly interesting rifle, built by an interesting smith, and proudly carried by an interesting writer and outdoorsman.

In addition to mentions of his trusty rifle, sears also frequently mentions a compass. Which makes sense since navigation is such a critical part of exploring the great outdoors. I do find it interesting that he doesn’t talk about maps much — perhaps back in the day you made your own. Either way we can only assume that the compass sears used was as simple and lightweight as possible.

“Nine men out of ten, on finding themselves lost in the woods, fly into a panic and quarrel with the compass. Never do that. The compass is always right, or nearly so.”

George Washington Sears, Woodcraft

Sears camp kitchen comprises five pieces of “tin ware” when camping… and only two pieces when “tramping” or “cruising.” The largest a 6.75” by 2” deep hand made tin pot (thickest tin available in the base). Next a slightly smaller pot that nests inside the large one, but is designed so in can be inverted and used as a cover for the first. Sears also carries two tin dishes and a 2 quart kettle… all of which nest in one way or another. Sears improvises flatware… forks are made from sticks and adding a mussel shell makes a “nice” spoon. Interesting… but I’ll definitley stick to my SnowPeak titanium silverware. Finally, Sears uses his Moose Pattern pocket knife to eat and everything is cooked over an open fire (or coals).

Sears also found himself fishing quite often and enjoyed a variety of fly rods, constructed from split bamboo. He professed that catching a trout on a fly was the preferred method of sportsman at the time. But, admits that he would stoop to using a hook and worm if needed.

Philosophies passed on to modern Conservationists

As both Sears and the US matured during the 19th century interest in recreational pursuits and the harsh realities of early capitalism spread like wildfire. Tanneries polluted the same streams where North Eastern anglers broke from British fly fishing canon. Developers, miners, and loggers clashed with figures like Ferdinand Hayden leading to the creation of Yellowstone National Park. And, Roosevelt helped establish Boone & Crockett to push back against widespread abuse of wildlife and natural resources in the West. The 1800s certainly provided us with a ton of history to discuss in the classroom but it also served as perhaps the first battlefield in the ongoing war to preserve nature for future generations. And, as you may know Sears spent most of his life on the frontlines of this figurative battle… writing about gear, cultural progression, and importance of protecting the backcountry. Things many of us, on both sides of the political aisle, care about now.

In his poetry, articles in “Forest & Stream” (now called “Field & Stream”), and in books like “Woodcraft,” shed light on Sears’ passion for wild spaces. Roughly five decades before Muir established the Sierra Club to protect wild spaces — Nessmuk publicly critiqued industries, like tanning, for carelessly damaging the environment. Most notably the North Eastern United States where textile factories, tanneries, and timber mills dominated much of the economic landscape. It’s pretty impressive considering that part of Sears’ writing career and the American Civil War both took place in the same decade. A love for the wild and a sense of personal and public responsibility for nature make Sears a bit of a legendary figure in modern American outdoor culture.

Beyond the clear cut – “stop destroying nature you greedy idiots” sentiment. Sears sums up a key area of his philosophy quite well when he calls his time in nature “getting away from the worry and hurry of the modern age.” A opinion that, unbeknownst to Sears, grows increasingly more accurate as decades pass.

If only modern outdoorsmen like myself could embraces his fondness for keeping things simple. He reached near clergyman levels of preaching about simplicity and minimalism when it came to camping and outdoor living. His philosophy emphasized carrying only what was essential for survival and comfort, which included a small cooking pot, a wool blanket, and the aforementioned knife and hatchet. This minimalist approach allowed him to travel light and move swiftly through the wilderness, forging a deeper connection with nature.

Early Life and Introduction to the Outdoors

George Washington Sears was born on December 2, 1821, in Oxford, New Jersey. He lived during a time when the United States was still expanding westward, and the wilderness was to Europeans a vast, uncharted expanse. His early years were marked by a deep fascination with the outdoors, which he inherited from his father and grandfather, both of whom were skilled woodsmen and hunters. As a young man, Sears honed his outdoor skills, becoming proficient in hunting, fishing, and woodcraft. He developed a deep connection with nature and the wilderness, which would shape the course of his life and career.

The Woodcraft Movement

George Washington Sears was not just an adventurer and writer; he was also a passionate advocate for conservation and responsible outdoor ethics. In his writings, he emphasized the importance of leaving no trace and respecting the wilderness. He believed in sustainable hunting and fishing practices and advocated for the preservation of wild places for future generations.

Sears’ commitment to conservation and responsible outdoor ethics contributed to the broader Woodcraft movement, which aimed to promote a deeper understanding of nature and an ethical approach to outdoor activities. His writings helped shape the values of the movement, emphasizing the importance of nature appreciation and responsible wilderness stewardship.

Legacy and Influence

George Washington Sears, aka Nessmuk, left an indelible mark on the world of outdoor literature and wilderness exploration. His writings continue to inspire outdoor enthusiasts, campers, and canoeists to this day. Here are some of the ways in which he has influenced the outdoor community:

- Lightweight Camping Philosophy: Nessmuk’s advocacy for minimalist and lightweight camping equipment has had a lasting impact on outdoor gear design. Many modern outdoor enthusiasts embrace his principles of simplicity and efficiency when selecting and packing their gear.

- Solo Canoeing: Sears’ pioneering solo canoeing adventures helped popularize the concept of solo wilderness travel. Today, solo canoeing remains a beloved outdoor activity, and his writings serve as a source of inspiration for those who seek solitude and adventure on the water.

- Conservation and Ethics: George Washington Sears’ emphasis on conservation and responsible outdoor ethics laid the foundation for the modern environmental and conservation movements. His writings helped foster a deeper sense of respect and stewardship for the natural world.

- Literary Contributions: Nessmuk’s writings, including his columns in Forest and Stream, continue to be cherished by outdoor enthusiasts and historians alike. His prose captures the beauty of the wilderness and the joy of outdoor exploration, making his works timeless.

Conclusion

I wanted to point out earlier that Sears didn’t really become the woodsman we all know until the spry age of 59 years. But, I hesitated because I didn’t learn that until I’d read quite a lot about him, and thought that I preferred it that way. Had I known from the start that he was far older than I am now I would have probably discounted him the way I do “experts” I find online these days. After all, before I graduated high school I accumulated more time in the Montana wilderness than Sears did in his entire career. But, I think that would have been foolish. Knowing what I know now… I’m actually a bit more impressed that he didn’t really start until nearly 60 years old. It’s an absolutely inspiring fact if you remove your own ego from the equation. I hope that at that age I’ll be picking up something new… and if that thing becomes the “thing” I’m known for 100 years later I’ll die an incredibly satisfied man.

That said, I’m a fan of Sears. Not necessarily because of his love of quality gear or minimalistic approach that I struggle to adhere to, but because he’s a bit of an underdog. Sears is an unlikely advocate of the wild. Small in stature, frail, and chronically ill… he’s not exactly the strapping mountain man we often associate with early US and Canadian outdoorsmen. But, that didn’t stop Sears from embarking on incredible adventures or speaking out against the damaging affects of the industrial age and consumerism. Quality, lasting gear, that minimizes its impact to the environment is a huge part of my life… Sears is probably somewhat responsible for that.

If you’d like to pay your respects to Nessmuk and his legacy you can visit him in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania (thanks to The Pennsylvanian Rambler for sharing the location and a bit of history). And, if you’re lucky enough to have a canoe… head to the south side of town to enjoy a paddle on Nessmuk Lake.